Sherlock Holmes and Watson are investigating rumours of a beast roaming the Yorkshire Moors. Holmes seems to have a plan, but he has not told Watson the details. It is just as well that Watson has complete faith in his friend.

They set up a tent, eat a small meal of bread and cheese, and lie back to wait the night out.

In the middle of the night Watson wakes up to find Sherlock staring up at the stars. He sees that Watson is awake and says to him, "What do you see up their Watson?"

Watson thinks for a moment, and quickly decides that the obvious answer, stars, is unlikely to be the one that Sherlock is expecting. He stares up into the abyss and finds himself thinking how peculiar it is that everything in the heavens is reduced to points of light.

He reminds himself that Sherlock has several coffee-table books in his rooms, the variety that are A2 in size and composed of glossy photographs taken by the Hubble Deep-Space Telescope. "I find the great whorls of stars somewhat comforting," Watson says. He instinctively believes that Sherlock will understand what he is referring to. Such is the nature of their friendship. "They look like pieces of art," he continues, "almost abstract splodges of white and yellow paint, like a pointillist painting in an incomplete state. I find it humbling to think that

all of that matter is not only clumped around points of space out there, but so far out there that we can barely see it." He pauses. After this, he concludes: "I see the unknown. I suppose it is what they call the 'Sublime'."

"Peculiar," Holmes mutters to himself, and looks around Watson's face expectantly. "Not that all those objects are not so incredibly far as to each be rendered a pointilistic dab in the firmament, my dear Watson," Holmes tells him. "Our third closest galactic neighbour, the Andromeda Galaxy, if it wasn't so obscured by closer things, would sit in the night sky more than three times the size of our moon." He pauses for effect while tracing a shape in the sky. "The problem is, it

is obscured by closer things and all that is visible - if you know what you're looking for; you really should read Brian Cox's Wonderful Universe for how to see it with the naked eye - is a vague bulge of stars."

"You mean, that the moon is in the way?"

Sherlock stays silent. Eventually: "One of the ways in which it is so obscured is that it lies some twenty three and a half trillion kilometres away from us. And by that same token, light can only travel at almost three hundred thousand kilometres per second, which makes our view of the Andromeda about two and a half million years out of our date."

Watson thinks about this while he scans the points of light glittering above him. He has never really given much thought to the objects up there.

"Imagine," Holmes suggests helpfully, "that someone on the other side of the world has asked you whether you like their new jacket. They send you a picture of themselves across the internet, and then, impulsively, they change their mind and decide to show you in person. They start running round the world in order to give you a twirl in your living room."

Watson thinks that over too. Eventually: "It might be a while before we get to see the current state of Andromeda's jacket."

Holmes sits up and lights a cigarette. "When the light from Andromeda that we see here on Earth today first began it's journey Homo Erectus had not even appeared on the scene. If so much could have changed here on Earth in that time, it makes you wonder what's really going on over there right now. But we can never know."

"What more do you notice?" he asks.

Assuming that Holmes meant in the light of the information he had just imparted, Watson tries to deduce. "Andromeda must be in a different place to the one in which we can see it?" he ventures.

"Your powers of observation are exemplary," Holmes tells him (though Watson hears a tone of sarcasm buffing the statement), and puffs on his cigarette. "Andromeda is moving in the radial direction of our Milky Way. This is known because almost all the galaxies in the observable universe are in red-shift (which is when the light waves coming from it are longer than expected) and this means that they are travelling away from our galaxy. But the Andromeda Galaxy is in blue-shift, meaning it is heading towards us, likely at about one hundred and twenty kilometers per second, a speed which would surely only be legal on the Autobahn. At this speed it is probably much closer than it seems, potentially about nine thousand, four hundred, and sixty one billion kilometers closer, a pitiful number astronomically, but still mind-bogglingly big for us." He thinks for a moment. "That is the equivalent of two hundred and thirty seven thousand million times around the circumference of the Earth. We just won't see it until the light has had the chance to travel that much less distance."

Watson stares up at the sky in wonder while the smell of Holme's burning tobacco blows past his face. And then he is struck by a thought, a brief one which he struggles to put into words. It has a persistence that demands that he does.

"Time is not the only thing obscuring our view," Holmes says pointedly, as if he has been peering into Watson's thoughts. "Not only are there

usually more Earthly obstructions, but all of the free-floating matter filling the space and the time between us and Andromeda is equally blocking on our view."

"So it is true then, that space is black because it has everything in it, just as if someone had scribbled across the heavens with all their coloured crayons and made the sky black," Watson says. "I used to believe that a lot of space was empty. That's what we are taught in school, after all, that space is a vacuum. "

"Neither of these ideas are completely true, my friend," replies Holmes. "There is a lot of matter in space. A lot of dust, a lot of debris. It's not all close enough to all be congealing into larger objects, like our old planet Earth, but there is enough of it in such vast areas as to obscure far objects. The night sky's colour isn't black because it contains everything, but because so much of it is nothing. So there is enough matter to render the sky black, and at the same time, so much of nothing that there is no light to colour it.

"Are you confused, Watson? There really are more important matters."

Watson is very confused, but he remains silent.

"Let's sort it out then," Holmes tells him, swung by a moment of pity for his friends inferior cognitive abilities.

"The thing about light and colour, my friend, is that physically, they don't work like a pack of crayons. If you make a black mess with all your colouring-in tools, you have created the colour black, but what you are actually seeing is an absence of colour. You have created a black mess that is absorbing the colours in the light spectrum. When we say the orange crayon is orange, what we are actually saying is that it is radiating every colour minus orange."

Watson felt that Holmes was facetiously enjoying the idea of young Watson with crayons too much.

"All of that debris that obscures our local (relatively speaking) view is like a windjammer on a microphone; it does not block our view of the lit up universe, so much as feather it. So the volume of debris we are talking about is far, far from as great as the space it fills. There might be enough stuff to blur much of Andromeda, or even our own Galactic Centre, to the naked eye, but we have space telescopes that can focus on sources of incoming light for long enough to circumvent this issue.

"What they see is that much of space is still black, and we are told it is because we can't see anything producing light. The furthest spied object is some two hundred and sixty billion light years away, and I would just like to take a moment to hammer home just how unimaginably far that is. We confront numbers of this size every day in relation to business and economics, which I think only serves to demean in our imaginations the actual amounts in question. Light travels at almost three hundred thousand kilometres a second. There are just over three million seconds in a year. So we are talking about three hundred thousand kilometres multiplied by three million seconds, multiplied by two hundred and sixty billion years." Multiplications rush through his mind. "That's more or less nine hundred and thirty six thousand trillion times round the Earth.

"Thank God we are doing this with rough numbers, because it might hurt a little bit to try and comprehend a more precise number with far fewer zeroes and far more of the other nine digits.

"So we know that there is matter out there as far as we can see, perhaps further. We don't know what lies out further. But we do know that we can't see it. Which can mean one of two things: 1. There is nothing else beyond that point. Maybe an edge to the Universe, maybe an infinity of nothing, but definitely no matter producing light. 2. There is still plenty of stuff out there, but it is so far out that there has not been enough time in the Universe for it's light to reach us yet. Both options are equally mind-blowing, do you not think?

"Let's not travel too far out and return to our view of Andromeda from Earth.

"Earlier I mentioned that Andromeda is in Blue-Shift, and most of the rest of the Universe seems to be in Red-Shift. Now, you remember the Doppler effect from school, the sound of a siren passing goes down in pitch as it approaches and passes. Essentially the same goes for light with the range of colours taking the place of the range of pitches. This needs vast distances and fast objects to be particularly noticeable, and still then machines are needed to actually see the difference because they are looking at the pitch intervals of white light, which, unlike the light reflected off a black object, is a radiation of all the visible colours. Curse our inferior eyeballs.

"Are you all to rights, my dear Watson? Despite my inferior eyeballs in this dark, I could swear your mien has lost a few shades of colour, and I doubt it is the chilly moor winds that has brought it about. Perhaps you have noticed something?"

Finally the words that Watson had been looking for have found there place and order. "I feel - somewhat - insignificant," he says.

"Science has a tendency to do that to people," Holmes says without much consolation. "Try not to think about it too much until there is less of the sky visible to intimidate you and tell me what can you infer solely from looking at the night sky tonight, Watson?"

"Why, I do believe that someone has nicked out tent."

"Very good, Watson."

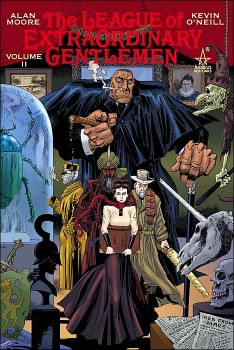

He's as dark as the Other can be. He's quiet and brooding in ways that can be attributed to philosopher and psychopath, both. He's wild, charged with untamed emotions. In a nutshell, this is what makes Heathcliff a romantic character. Let's ignore the fact that he quickly becomes an enraged psychopath with horrific outbursts of violence and the sort of patience and will that is required to destroy two whole generations of friends and family.

He's as dark as the Other can be. He's quiet and brooding in ways that can be attributed to philosopher and psychopath, both. He's wild, charged with untamed emotions. In a nutshell, this is what makes Heathcliff a romantic character. Let's ignore the fact that he quickly becomes an enraged psychopath with horrific outbursts of violence and the sort of patience and will that is required to destroy two whole generations of friends and family. He's as dark as the Other can be. He's watchful and carefully measured in ways that can be attributed to genius and psycopath, both. His emotions are wild, but roped in with a visible but exerting sense of self-control. This is Snape, the tragic anti-hero. Let's ignore the fact that he spends most of five books being the cruel tormentor of his true-love's child.

He's as dark as the Other can be. He's watchful and carefully measured in ways that can be attributed to genius and psycopath, both. His emotions are wild, but roped in with a visible but exerting sense of self-control. This is Snape, the tragic anti-hero. Let's ignore the fact that he spends most of five books being the cruel tormentor of his true-love's child.