It's as plain as the halo on your head and your forked tail whipping about in your wake that the world is neither black nor white. It would be lovely if the world could be split into binary so neatly; good triumphs over evil, right is right, and wrong receives punishment, possibly followed by redemption. Instead, all it takes is a few moments thought, or less, to realise that the moral lens is not polarised so brightly. The ethical world is actually coloured in shades of grey.

This is one of the reasons I love Alan Moore, because he knows this, and shows this. He avoids prescribing any one particular idea of correctness, and instead paints a world in layers of individual morality. One of the most commendable aspects of his multi-faceted retelling of the Jack the Ripper killings is the novel's refusal to be pinned down by specific morals. Instead he pointedly draws attention to the range of ethical codes available, both in person and in time. The irony of such moral complexity being portrayed in black and white ink drawings shouldn't be lost on anyone.

But then, JTHM is an extreme example. 60 years ago almost no publishers would have been willing to commit to putting it in print for fear of the backlash; accusations of bad taste, and lack of humanity, or any of the denunciations that Mary Whitehouse ever aimed at anything. Back then and before, during the Golden Age of the comic book, the world was a more idealised place. This was a world still giddy with huge social and political upheavels. It was still coming to terms with the boundary crossing Modernist movement. This was a world that unquestioningly embraced the vigilante heroics of the super-wealthy Bruce Wayne, who now has one of the most recursive origin stories.

For almost 70 years the story of a handful of characters has been reimagined for, and retold throughout every decade, sometimes slowly and sometimes drastically, morphing to fit the appreciations of the popular culture. You could almost believe there was nothing new to say in these stories if it was simply the story that people read for. Except that retroactive story-telling is symptomatic of much deeper issues.

Batman's appeal is generational and has more to do with the world around us than the world in the story. In the beginning he drew his literary power from the audience's new found love of superheroes and strains of the more complex underworld that preoccupied detective noir. Whereas the less prolific superheroes stole their reader's imaginations with their simple colourful battles of good vs. evil, Batman was ruining the criminal classes on the basis of a deeply ingrained vendetta. He was fighting for selfish reasons. This man was a self-serving soldier, a genuine human Ubermensch, reflecting the time's belief in a will to power.

The 60's and 70's were a time of two polar outlooks: the colourful, liberal, pacifist movement, and the creeping reality of the Cold War. Batman's darker overtones were overcompensated for by the garity of the drawings and the campness of the stories. This was a time when Batman was able to permit absolution for Catwoman's long history of theft, destruction and death. A far step from the Batman of the 80's who enjoys playing the Joker's dark, psychological games. What on Earth happened in the time between these two same characters that changed the appeal? Was it fatigue from the ever present Cold War that left people beginning to accept a darker, more brutal reality? Or the death of 'unbiased news' and the rise of a sensationalist mass media?

The Batman's of Alan Moore, Frank Miller and Grant Morrison are miles away from his fellow superhero of the 1930's, the pillar of pure goodness that came from Krypton. And the rest of the modern comic book world is just as far, so much so that almost anything more complex than good vs. evil falls into the graphic novel category.

Yet, however complex the issues of the Batman stories have become they are still swamped with dichotomy. Rather than asking who is good and who is evil, they ask is there good, and is there evil? How much of evil is fear and anger, and how much of good is self-control and reason?

In fact, the Batman novels of the 80's onwards have a preoccupation with feathering the lines between good and bad. They don't offer a bad character redemption, but ask you to give it, while pushing the concept of the tragic hero into the vacuum of anti-hero. Whereas the comics before riffed on the previous creators' stories, adding details to previously told stories, the 80's marked the beginning of the reboots and full retroactive changes, the ideal technique for updating the ideas for a completely changed audience, for mirroring the new audience's beliefs.

In fact, the Batman novels of the 80's onwards have a preoccupation with feathering the lines between good and bad. They don't offer a bad character redemption, but ask you to give it, while pushing the concept of the tragic hero into the vacuum of anti-hero. Whereas the comics before riffed on the previous creators' stories, adding details to previously told stories, the 80's marked the beginning of the reboots and full retroactive changes, the ideal technique for updating the ideas for a completely changed audience, for mirroring the new audience's beliefs.Take X-men's Magneto, a sixties style megalomaniac Bond villain, until '78 when he receives a backstory that touches on events and issues with deep cultural scars. It could easily be tasteless using the Holocaust to explain a superbaddy's behaviour, and yet it marks a significant engagement with the real world in the X-men's long-running theme of racism. It's asking questions about the cause and effect of racism at a time when various civil rights movements of the 60's and 70's were pushing racism into its visible yet unmentioned institutional and commercial forms of the 80's.

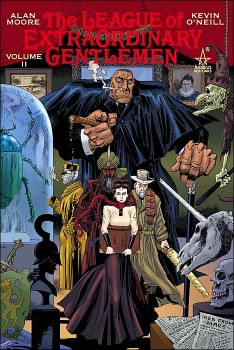

Take Alan Moore's League of Extraordinary Gentlemen from the late 90's, stories that take the anti-heroes of 19th Century popular literature and puts them in the position of traditional comic-book heroes. Finally we have a comic book that shows us what we feel about the reality of being a hero, that the important actions are the ones taken by the unrecognised, and that heroic qualities are attributed by others. It marks (along with many other recent graphic novels, these just happen to be my favourite) the journey that the comic book has taken us from old-fashioned, conservative prescriptive ethics to the modern taste for descriptive ethics, a journey that the traditional novel took over 3 centuries ago.

It pleases me that the creators of comic books have realised the potential for moral and emotional complexity that the medium held, and that an adult market was willing to embrace the move. We always knew the Devil was more interesting than the Angels, perhaps because it's a challenge to look in the dark but no difficulty to be blinded by the light.